The Other Elizabeth: Ferret Face vs Marilyn Monroe

You never step into the same river twice – but two different rivers might witness two surprisingly similar lives! ‘So, you write about Elizabeth,’ people said, when I told them about my next project after the success of ‘Tsarina’, assuming yet another tome about England’s most famous Tudor Queen.

Time to take the Path less travelled

Err, yes, but no. There have been so many books – novels and biographies alike – about the Tudors that they become tiresome, and even the War of the Roses – think Lancaster and York Yore – has been overexploited. It is time to take the Path less travelled – the ‘Tsarina’ series explores the unique century of female reign in Russia. Like in the case of Tut-Ankh-Amun, whose tomb was always there, but whose predecessors and successor shed so much light that his reign slid in the shadows of history, the early Romanovs are deliciously undertreated.

<img class=”size-full wp-image-30464″ src=”https://russianroulette.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/outlook-odakqqec.jpg” alt=”Tsarina’s Daughter by Ellen Alpsten” width=”1080″ height=”1080″ /> Tsarina’s Daughter by Ellen Alpsten

I feel so lucky to have unearthed ‘my girls’ for Western literature as much as Howard Carter excavated the boy-Pharaoh, doggedly believing in his destiny. ‘Tsarina’ was the first novel ever to tell of the astonishing rise of Catherine I from serf to Empress while charting Russia’s metamorphosis from backward nation to superpower.

Once more, ‘The Tsarina’s Daughter’ is the sole novel about the stunning life and rise to power of Tsarina Elizabeth Petrovna Romanov, the daughter and only surviving child of Peter the Great.

Elizabeth lives the opposite of her mother’s life: ‘Lizenka’ as her father called her, falls from riches to rags, before triumphantly rising from rags to Romanov. As the very unlikely love of her life towards a Ukrainian Shepherd Alexei Razumovsky makes her become who she is, she takes what is hers – the throne of her parents – even though it comes at a terrible price of imprisoning an infant-tsar Ivan VI for life. Hers is one wild, seductive ride of a story, and she is nothing short of a rollercoaster called Romanov.

The thin line between inspiration or imitation

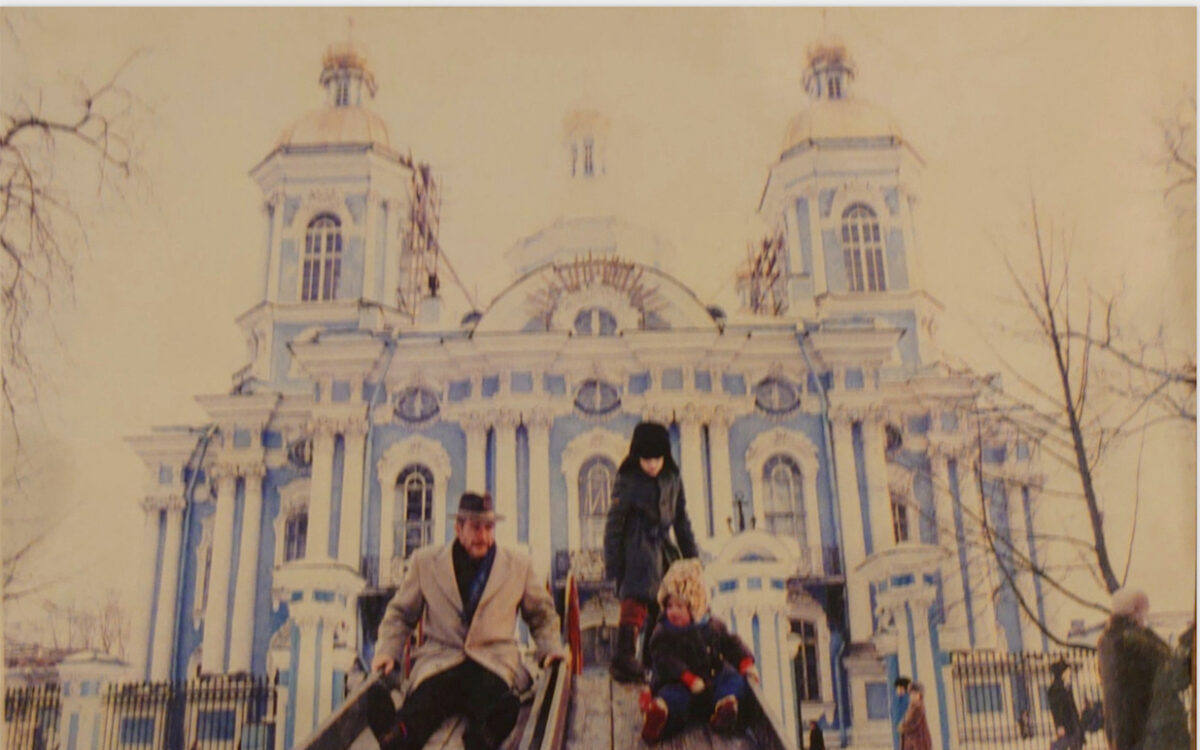

Two rivers, two women called Elizabeth – indeed there could be no better place to write ‘The Tsarina’s Daughter’ than walking along this river, whose strong currents opens a door to world history, and leads towards and through a great, bustling city.

Am I talking the ice-green waves of the Neva, who, come spring, were able to swell straight into St. Petersburg’s newly built palaces, as if a rainbow had morphed into stone; filling canals and glittering beneath bridges, its surface reflecting the clouds as a dreamlike city in the sky as Dostoevsky so beautifully put it?

Or is it the slate-coloured, more sullen, vast river Thames we think of, the artery of London bustling body, from its notorious back-alleys to the respectability of the City and the green open spaces of the Royal Palaces, such as Richmond once was? Both cities are as much linked as my leading Lady Elizabeth is to her Tudor namesake: Peter the Great’s ‘Paradise’ was a fruit of his visit to London, where he learnt all about the infrastructure, organisation, and administration of a modern city that there was to learn before he set to work, planning his ‘Paradise’, or his ‘New Jerusalem’.

In January 1698, he had arrived ‘incognito’ with an entourage of, amongst others, four dwarves, six trumpeters, a monkey, and a guard of 70 men matching his unusual height – he stood seven feet high in his boots. The Tsar’s raucous behaviour shocked the puritan King William to the core: London’s ‘Muscovy street’ is a reminder of Peter’s drunken forays, and unique as it is the only road in the UK called like that. When the Tsar could be finally convinced to leave, he had visited the Royal Mint, the Royal Observatory, the Woolwich Arsenal, Oxford University, and the shipyards of Deptford.

Let it rip!

His quarters, however, had to be renovated top to bottom: Like an early member of a rock band, Peter unleashed hell in the mansion offered to him, home of the famous diarist John Evelyn. The Tsar’s entourage let it rip. In their three months stay, they covered the carpets in ink, excrement, and grease, used pictures as a target for knife-throwing practice and pistol shooting alike, burned dozens of chairs, and pushed each other in wheelbarrows through the ornamental hedges that were Evelyn’s pride and joy, howling with laughter. Curtains, rugs, and bedlinen were torn, and hundreds of stained-glass panes were broken.

The housekeeper wrote to Evelyn to complain of ‘a house full of people right nasty’. Architect Sir Christopher Wren was called in to survey the damage after they had gone which he estimated to be around £250, equalling £60,000 GBP in today’s money. The royal British purse gnashed its teeth but picked up the bill for the damage. Before leaving the Tsar rewarded his mistress, London singer Letizia Cross, with £500.

She felt short-changed, he complained to have overpaid.

Bloody Bedtime and Barren Bodies

Two realms, two rivers, two cities home to two royal ladies named Elizabeth – yet their similarities are more inspiring and eerie yet.

Both were born as second daughters of a relatively young royal dynasty; the Tudors and Romanovs had to assert themselves.

The princesses were blessed or burdened with overwhelming father figures – imagine Henry VIII or Peter the Great doing bedtime, blood on their hands, having executed close friends and advisors or cumbersome eldest sons and heirs!

But both their mothers were second wives of lesser lineage, while a first, official spouse, who was respected by the establishment, survived: Anne Boleyn and the former serf and washer-maid Catherine I of Russia were shunned by the church and internationally derided.

‘The Empress of Russia is mouse-shit who wants to be a pepper-corn’, the mistress of Louis XIV said derisively about the illiterate Catherine.

As both girls were at times considered illegitimate – Peter the Great married Catherine when Elizabeth was three years old, and Elizabeth Tudor suffered from her mother’s beheading – they were not intended to rule. Instead, they were considered for an international match, preferably with a French Royal groom.

Fate decided otherwise – and from then on, the young women’s survival resembled a tightrope walk over treacherous waters. Latent terrorism reigned at either court, where the Princesses had to dodge the jealousy, fear, and suspicious hatred of an older, less popular, and less gifted female monarch – Bloody Mary and Anna Ivanovna.

Coming of age, they applied charm and cunning – until an unlikely love story made them become who they were. In the case of ‘my’ Lizenka, loving her warranted capital punishment: one lover had his tongue torn out and was muted to Kamchatka as a simple soldier.

Yet as rulers both women remained unmarried and accepted their childlessness as the ultimate price of their independence. As they lay dying in a riverside palace – in Richmond, and the Hermitage – they left their throne to a little loved nephew.

The Difference is delicate, and delicious.

Were the two Elizabeths like twins separated at birth, and by 175 years? Not quite – the major difference is delicate, if not delicious. Hilary Mantel calls Elizabeth Tudor ‘Princess ferret face’, whilst the painter Louis Caravaque was smitten by the Romanov daughter, describing her as ‘Europe’s loveliest Princess’, and painting her akin to a young Marilyn Monroe, dewy eyed and rosy-cheeked.

Whilst the Tudor Queen fiercely reigned in her passions, styling herself as the chalk-and stone-faced ‘Virgin Queen’, the tsarevna had inherited her parent’s sensuous appetites: Peter the Great had plucked the love of his life – Lizenka’s mother – from a pack of prisoners, noticing her ‘animal-like warmth’.

‘The Tsarina’s Daughter’ had ‘not an ounce of nun’s flesh on her body,’ one shocked foreign envoy reported as Elizabeth cavorted through court, before sighing: ‘All her flaws are in her morals, not her appearance.’

A woman like the Slavic Spring

What do I love most about Lizenka? Whilst Elizabeth Tudor stuck to the mores of her times, my heroine in ‘The Tsarina’s Daughter’ acts like a modern woman, surpassing her times’ stringent expectations. Her force was compared to the Slavic spring, the Ottepel’ – no wonder I thought of her when I walked, thinking and plotting, and the daffodils push through all over the London Parks, golden and irrepressible.